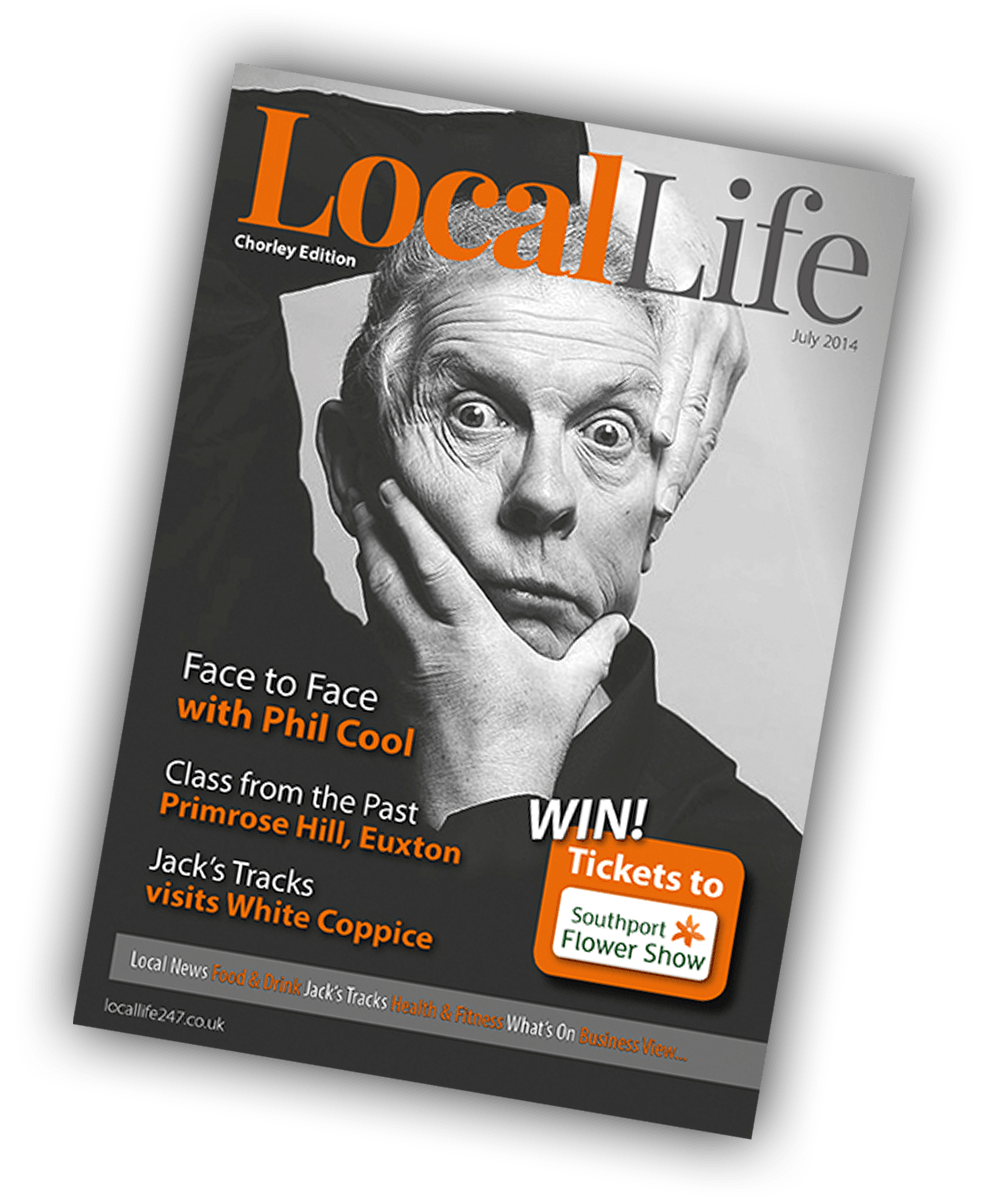

Canal Mill workers circa 1950, provided by Pamela Brown

Although now often relegated to shopping outlets, dusty museum displays, or urban living for aspiring young professionals, mills have always been integral to our local heritage. From the water-driven mills of the eighteenth century to the surge in mechanisation and the eventual decline of the industry, these great structures continue to have a place in the hearts of locals.

The closure of Chorley’s Botany Bay (previously Canal Mill) in February pending its extensive redevelopment into a modern outlet village is a blow indeed to Lancashire’s milling heritage. Mills undeniably shaped the county’s industrial and economic landscape in the 1900s, when the Industrial Revolution settled its focus on textile manufacturing. Somewhere along the line, Lancashire became synonymous with cotton milling, from the invention of James Hargreaves’ spinning jenny in Oswaldtwistle back in 1770 to towns like Burnley making their names in cotton. In fact, the industry expanded enough that the government was forced to introduce a policy to slow its growth down in 1959.

The detrimental effect milling had on its workforce is well-documented. Channel 4’s TV adaptation The Mill shed light on the conditions working-class people faced post-Industrial Revolution at Quarry Bank Mill in Cheshire. It’s easy to look back on the industry now with rose-tinted lenses, but with mechanisation came abhorrent working conditions, child labour and many accidents.

Many workers reported ‘mill fever’ in their first few weeks of employment; the dust, chemicals and claustrophobic environment landing a hard knock to the immune system. A lot of mill girls communicated solely by lip reading due to the supremely high levels of noise from nearby machinery.

That’s without mentioning that textile milling also contributed to the frequent smog that loomed over industrial towns during the latter part of the twentieth century, with air pollution from factories turning the streets into smog-bound ‘pea soupers’. The 1950s were especially notorious for this phenomenon – although chiefly arising from the burning of coal, bleaching, sizing and bast-fibre processing in cotton mills played their part too.

In Chorley, tragedy truly struck in 1951, when a man was killed at Smethurst Mill following the shattering of an engine flywheel. A 300-pound mass of steel came close to severing the legs of Adreina Padovan from Italy, and injured a further thirteen people.

Despite the turbulence of Chorley’s milling history, it’s easy to forget the architectural prowess and innovation that went into the construction of similar buildings around Lancashire and what is now Greater Manchester, and to dismiss milling as a brutal stopgap into modernisation. Faster processes revolutionised the industry and Britain for the better, and brought employment and money to Lancashire instead of relying on foreign imports.

Despite the integral part milling played in local heritage, many of Chorley’s mills have fallen into disrepair – with renovations deemed too expensive to keep Botany Bay in its current state, and the fire-ravaged remains of Lower Kem Mill attracting tourists at Cuerden Valley Park, while others like Mavis Mill in Coppull have been converted into business spaces. But, whether hotspots for urban exploration or monuments lost to time, many of these imposing structures have a lot more to offer – and it’s high time they got the appreciation they deserve.

Canal Mill

Constructed in 1855 during the Crimean War, Chorley’s very own Canal Mill has been a draw for visitors from far and wide for over twenty years. It was original built for Richard Smethurst, the son of a local cotton milling pioneer. Smethurst died in 1860, and his mill passed on to his business associates William & Charles Widows.

The Lancashire Cotton Famine of 1861-65 led Canal Mill to briefly cease production in 1861, caused by overproduction in unstable international markets. The demand for raw cotton slumped just as ports were overwhelmed with an influx of it, causing the price to collapse. Many workers became unemployed, forced to attend soup kitchens and appeal for meal and coal tickets. Eventually cotton imports were restored, and the mill continued production into the 1950s.

Men were employed on the top floor of Canal Mill as spinners, while women worked as creelers on the lower floor preparing the bobbins. Many workers recount happy memories of the mill, including combing-room worker Pamela Brown who recalls swimming in the nearby Leeds & Liverpool Canal on hot summer days.

Canal Mill eventually closed in the 1950s, around the time of the introduction of the Cotton Industry Act of 1959, when demand for cotton failed to meet the overwhelming amount of production. The Act looked set to rejuvenate Lancashire’s textile links, with the view of reorganising the cotton industry by reducing the number of spindles in operation while making some workers redundant in order to reduce unneeded output. Canal Mill, however, didn’t survive this reorganisation, instead becoming a chicken farm in the 60s and then a repair workshop for trucks in 1968.

In 1991, Gilbraiths Commercial Limited ceased operations and in 1992 planning permission was granted to turn Canal Mill into a themed visitor attraction which would draw people to Chorley for decades to come. Botany Bay Villages opened in December 1995, offering five floors of shopping, restaurants and an indoor play centre for children. Still, the mill was allegedly haunted by the ghosts of mill workers, with visitors experiencing a crushing sensation in their limbs as though being trapped in the vice of cotton spinning machinery.

Botany Bay officially closed in February 2019 to be renovated into a modern outlet village and 288 homes.

Grove Mill

Owned by Botany Bay’s very own Tim Knowles, the Grove Mill site in Eccleston began its life in the seventeenth century, when it existed as a rural woollen processing farm. A cotton mill was constructed on the site in 1845, and by 1861 employed around 300 workers in spinning and weaving.

Grove Mill encountered a few financial difficulties in the latter part of the nineteenth century, and continued to produce cotton until the 1980s, surpassing Canal Mill through the slump of the 1950s and the industry’s subsequent reshuffling. It exists now as antiques emporium Bygone Times – and as a home to several ghosts.

Reports of two unruly child spirits outside a meeting room used by the Wesleyan Church sparked rumours of this ghostly activity at Bygone Times. Paranormal investigators also recorded seeing a man pacing up and down, and the face of a lady in a window. A ghost trail is available for children to investigate these goings-on at Bygone Times.

Lower Kem Mill

Whittle-le-Woods has a tragic milling past. Home to its own bleaching and dyeing works from the 1700s, the area which is now part of Cuerden Valley Park is now a mere ruin of what once was. What in all likelihood began as a cottage industry enterprise expanded into a larger mill in 1784, with several workshops, printing shops and dye rooms scattered about, with dwelling houses for the workers.

The mill became known as the Kem Mill Printworks, and employed around 170 workers. The mill expanded between 1881 and 1896 to cope with the growing cotton industry, including the construction of a 150 foot chimney.

Tragedy struck on October 17, 1914, when a fire broke out in the machine room. The fire brigade were summoned but the flames continued to spread, enveloping the roller room, and the office before the walls and roof of the main building caved in. The resulting smoke was visible for miles around, drawing spectators from around the area, and eventually the fire was put out, leaving behind smoking debris and thousands of pounds of destroyed machinery. Aside from the chimney, which was saved, the scene was one of utter destruction, and Kem Mill was no more.

The site was used for farming until 1972, when the chimney and remaining buildings were demolished. Several archaeological digs uncovered artefacts from the site’s milling days, and the ruins of Kem Mill Printworks were refurbished using grant money . They are still visible today to visitors to Cuerden Valley Park.

Birkacre Mill

1777 saw the ‘Factory System’ arrive at Birkacre along the River Yarrow. Edward Chadwick constructed a purpose-built cotton mill – one of the first mills to stray from domestic spinning and weaving methods in Lancashire, and the first mill in Chorley.

The mill was leased to Richard Arkwright, who fitted it out with his patented machines and drove power to it using a waterwheel. Arkwright was also responsible for the water spinning frame in 1767, which ran on water power and produced stronger and harder yarn than the spinning jenny.

Despite its revolutionary technological strides, Birkacre Mill was perhaps most famous for the riots it was involved in. In 1779, a mob of Luddites – a secret, oath-based organisation determined to stop the ‘fraudulent’ use of machinery in place of a manual workforce – got word of the mill’s innovation and he marched to stop it.

The protest turned violent a few days later, when the mob broke into the mill and destroyed its interior. They were met with gunshots from the mill’s forces but the mill’s wooden machinery was easily submerged in flames, killing at least one of the Luddites in the process.

Chadwick did rebuild the mill shortly after, and developed into calico printing, dyeing and bleaching. It eventually ceased operation in 1939, and in the 1980s the derelict land was reclaimed by Yarrow Valley Park, and transformed into parkland.

Thanks go to Chorley Mills (www.chorleymills.org) for providing images.